Frequently asked questions

In the UK, 40,000-50,000 operations are performed each year to remove gall bladders.

Why do gallstones form?

Blank

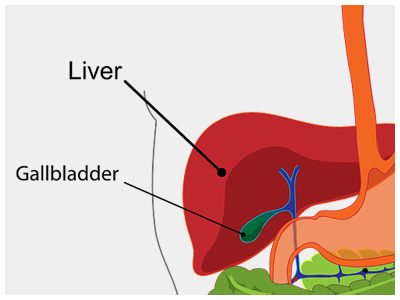

What is the gall bladder and what does it do?

The gall bladder is a small bag, roughly the shape and size of a pear, that sits underneath the liver, on the right side of the abdomen.

The liver makes bile. The bile flows out of the liver through a tube that is called the common bile duct. This emerges from the under surface of the liver, and is roughly the thickness of a drinking straw. The gall bladder hangs off the bile duct at this point, just after it has emerged from the liver, a bit like a pear hanging from a branch. The bile duct then runs downward and enters the duodenum (a part of the intestine) where the bile mixes with the food. The pancreatic duct, which drains the digestive juice from the pancreas, also empties into the intestine at the same place.

The gall bladder stores some of the bile that is produced by the liver. After a meal, especially a fatty meal, chemical signals go to the gall bladder, which then squeezes out the bile it has stored, into the bile duct, and from there into the gut.

Bile contains water, cholesterol, fats, bile salts, proteins, and a yellow pigment called bilirubin. It helps in the digestion of fat.

What are gallstones?

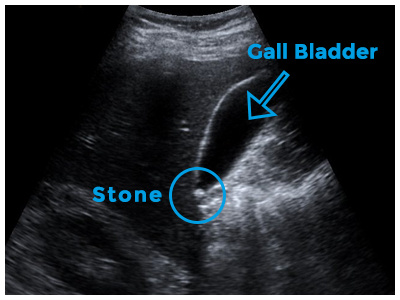

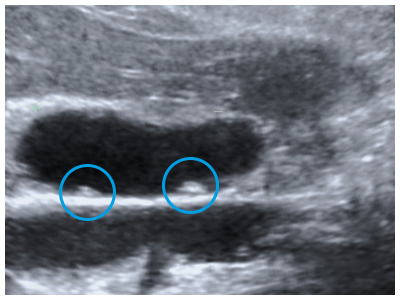

Gallstones can be cholesterol stones, pigment stones or a mixture of the two. Cholesterol stones are largely made of solidified cholesterol. Pigment stones are dark stones made of bilirubin. The majority of stones are mixed stones that contain cholesterol as well as pigment.

The gallbladder can develop just one or two large stones (some can be as large as a golf ball), or lots of tiny stones (as small as grains of sand).

Why do gallstones form? Are some people more likely to develop gallstones?

In general, those over 60 (men and women) are at a higher risk of developing gallstones.

People who are overweight are more likely to form gallstones.

Excess estrogen from numerous pregnancies, hormone replacement therapy, or birth control pills may increase cholesterol levels in bile, slow down gallbladder emptying, and lead to gallstones.

People who have biliary infections (for example liver flukes in the tropics) can develop gallstones.

Individuals with hereditary blood disorders such as sickle cell anemia (in which too much bilirubin is formed due to the breakdown of blood cells) are more likely to form pigment stones.

Going on a diet (with rapid weight loss) and certain cholesterol-reducing drugs can also increase the risk of gallstone formation.

A high level of cholesterol in the blood is not necessarily a factor in the development of gallstones.

Can I do anything to stop gallstones from forming in me?

Those who already have pain from gallstones often find that fatty or oily food can trigger the pain. So a low-fat diet can help keep the pain at bay. Gallstones are not related to stones in other parts of the body, particularly stones in the kidneys or in the urinary bladder.

What problems can gallstones cause?

Blank

What symptoms can gallstones cause?

The milder symptoms of gallstones include abdominal bloating, belching, indigestion, and nausea, usually after a meal.

More severe symptoms include attacks of abdominal pain and vomiting. The pain is usually in the upper abdomen, often more to the right, and can move to the right shoulder blade or shoulder tip. It may come on after meals, especially with fatty foods. This kind of pain is called biliary colic. Most attacks of biliary colic settle after a few hours.

Gallstone can cause symptoms similar to those of a heart attack, appendicitis, bowel obstruction, peptic ulcer, hiatus hernia, pancreatitis, hepatitis and occasionally biliary cancer. It is therefore very important that the correct diagnosis is made.

What complications can arise from gallstones?

Acute cholecystitis is a medical emergency and requires admission to hospital. Treatment has conventionally involved pain killers and antibiotics to settle the acute inflammation, followed several weeks later by an operation to remove the gall bladder. Of late, if the diagnosis has been made promptly, surgeons may resort to immediate surgery.

Acute cholecystitis caused by aggressive bacteria can cause the gall bladder wall to rot and disintegrate, and the gall bladder may then burst into the abdominal cavity or into an adjacent bit of bowel.

If there have been repeated attacks of inflammation, the gall bladder becomes chronically inflamed, shrunken and scarred. This is called chronic cholecystitis. If the outflow from the gall bladder is totally blocked by a stone it may become a bag full of stagnant bile (a mucocoele) or a bag of pus (empyema).

Gallstones slipping out of the gallbladder into the bile duct can block the flow of bile and cause obstructive jaundice. If you have severe abdominal pain, chills, fever, yellow discoloration of the eyes or skin, or pale stools, you should urgently consult a doctor.

Gallstones passing down the bile duct may also cause inflammation of the pancreas – acute pancreatitis. This is a medical emergency. Most attacks of acute pancreatitis settle down, but it has the potential to escalate into life-threatening complications.

Can gallstones cause gall bladder cancer?

Gallstones are a risk factor for gall bladder cancer, though the mechanism is unclear. Usually patients with large stones of long duration are at increased risk for cancer. More than the stones themselves, incomplete emptying of the gall bladder and the chronic inflammation that goes with it may have a role to play in initiating the cancer.

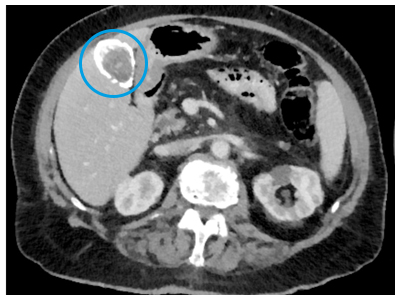

Calcium deposits in the wall of the gall bladder (a consequence of chronic inflammation), described as Porcelain gall bladder, increase the risk of gall bladder cancer. The picture on this page shows a CT scan, with a porcelain gall bladder clearly visible (you can click on the picture to enlarge it).

Chronic Salmonella infection of the gall bladder, which predisposes to gallstone formation, can predispose to gall bladder cancer.

Patients with choledochal cysts (a focal or diffuse bulge in the bile duct) or abnormalities at the point where the pancreatic and bile ducts join and enter the bowel are also known to be at increased risk for gall bladder or bile duct cancer.

Sometimes patients are found to have polyps (little growths) on the lining of the gall bladder. Polyps are generally benign, but patients with a single, large (> 1cm) polyp are more likely to develop cancer within their polyp. See below for more information about gall bladder polyps.

How are gallstones diagnosed?

Blood tests are done to check if the liver is functioning properly, and particularly to look for evidence of biliary blockage or infection.

Occasionally, other tests may be required, such as CT scan, MR scan and MR Cholangiography (MRCP), or radio-isotope tests such as HIDA scans.

If there is a suspicion that stones have slipped out of the gallbladder into the bile duct, Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) may be required. The patient has a long, flexible, tube camera called an endoscope guided down the gullet, through the stomach into the bowel. The doctor then injects a special dye into the bile duct, and x-rays show up stones in the duct. The stones in the bile duct can then be removed. ERCP is usually done under sedation, without need for a full anaesthetic, and patients rarely need to stay in hospital for this. Stones in the gall bladder cannot be removed by this method.

An MRCP scan can also show up stones in the gall bladder and the bile duct.

Can something else (other than gallstones) cause similar symptoms?

What are gall bladder polyps?

Polyps that are single, sessile (do not have a stalk), and are 1 cm or more in diameter should be deemed as suspicious i.e. they may develop into cancerous (malignant) growths. Also, polyps that have developed in older patients (over the age of fifty years), developed in association with stones or are associated with symptoms, are at a higher risk of being malignant or subsequently turning malignant. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (keyhole surgery to remove the gall bladder) is the treatment of choice in these patients, unless the suspicion of malignancy is high, in which case open exploration is preferable, with preparation for extended resection if necessary.

For polyps that are deemed low-risk, our practice is to recommend follow-up at first with regular ultrasound scans every 6-12 months, which can stop after 2 years if they remain unchanged.

Can you get pain from the gall bladder even if there are no stones?

Can you get inflammation of the gall bladder even if there are no gallstones?

There is a condition called acalculous cholecystitis (calculus means stone; acalculous means without stones, as opposed to calculous, which means in association with stones). This may develop acutely in patients in intensive care who are ill from other causes, or whose immune systems have been suppressed. Very rarely it occurs in elderly or frail people with a poor circulation.

Surgery for gallstones

Blank

What is the recommended treatment for gallstones that are causing symptoms?

If my gallstones have never caused me any trouble, do I need an operation?

There may be some unusual circumstances where treatment may be recommended for silent gallstones, such as a strong suspicion of cancer, or a patient who will not cope very well with gall bladder inflammation if it develops – these require discussion with your doctor. Once gallstones have started to cause symptoms it is likely that they will continue to do so.

Is there an alternative to surgery?

Lithotripsy (using sound waves to break up the stones) can work well for kidney stones, but does not work for gallstones. After they have been broken up, the gallstones may not flush out of the gallbladder. In fact the debris can clog the bile duct and cause additional problems.

Endoscopy (ERCP) can get rid of stones in the bile duct, but stones in the gall bladder cannot be removed this way.

Leaving the gallbladder behind and doing an operation to only remove the stones will mean that the stones can form again. So an operation to surgically remove the gallbladder is the best treatment for gallbladder stones that are causing symptoms. You may see advertisements for remedies to “flush out” gallstones. These treatments are unproven, and have no hard scientific evidence to support their use. It is possible that these remedies have benefited some individuals, but to be labelled effective, a treatment has to be shown to work in a majority of patients, when compared against another “standard” treatment or against a placebo.

How do I find a "good" surgeon?

What does a keyhole operation to remove the gall bladder involve?

Cholecystectomy is usually carried out by the laparoscopic (‘key hole’) method. Three or four small cuts are made in the abdomen. Each of these cuts is generally no more than 1 cm in length. The abdomen is then blown up with carbon dioxide (CO2) gas. This lifts the abdominal wall upwards, and gives the surgeon space to operate. The gall bladder is removed using a special laparoscopic camera and instruments. The operation usually takes 30 to 90 minutes. At the end of the operation the carbon dioxide gas is let out.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is preferable to open surgery because the cuts made are much smaller, postoperative pain is less, hospital stay is shorter, and the return to normal activity much quicker.

A general anaesthetic is the norm.

Many patients undergo this operation as a ”day case” (i.e. they do not stay overnight in hospital). Very few require more than one night’s stay in hospital.

Why use CO2 to inflate the abdomen?

Carbon dioxide is soluble in blood, so if it does get into the blood circulation, it will dissolve. Inert gases such as nitrogen (or air, which is 80% nitrogen) do not dissolve in blood, so gas bubbles can float about in the circulation and get to the lungs (this is called air embolism). Oxygen does dissolve in blood, but it is flammable. Electrical cautery is routinely used to stop bleeding, and that can cause sparks. If the tummy is full of oxygen, that would risk an explosion (!). Hence carbon dioxide.

Can I have a keyhole operation done through a single cut?

Must I have general anaesthesia?

This involves an injection into a vein in your forearm, and you then drift into a deep sleep. While you are unconscious the anaesthetist gives you medications to make your muscles go limp, and controls your breathing with a help of a ventilator (a machine that pushes in oxygenated air into your lungs a certain number of times each minute, through a tube that has been placed in your throat). This may sound complicated, but it is a very safe process, and your bodily functions (especially the workings of your heart and your lungs) are monitored very closely all along – the picture alongside shows a monitor screen. You wake up at the end of your operation like waking up from deep sleep.

During the operation your surgeon will also inject some local anaesthetic into your cuts, which usually lasts for 6-8 hours.

Steps before gallstone surgery

Blank

What should I do before the operation?

Please discuss with your surgeon what you should do about medications that you are on. If you are on medicines that affect your clotting (such as heparin or warfarin) you will need to stop them beforehand. You could continue to take Aspirin but again you should discuss this with your surgeon.

It is advisable to stop taking the contraceptive pill 4 weeks before an “elective major operation”. The same does not apply to day surgery (laparoscopic cholecystectomy falls into this category). If you are on the pill, please ask your surgeon if you should stop taking it.

Is there a particular diet I should follow if I have gallstones?

If certain fatty foods have triggered your attacks of pain, you should obviously avoid those. In general, you will be better off if you adopt a low fat diet. This will not get rid of your gallstones, but may reduce the severity and frequency of your attacks of pain. Here are some tips:

How to eat

Eat less

Eat only when hungry; stop eating when you are full

Do not feel obliged to eat every course and finish every portion

Do not “graze” just because food is there around you

What to eat and what not to eat

Eat mainly plants; less meat

Eat fish or poultry in preference to red meat, as red meat contains more fat.

Eat home cooked food (where you can control what goes in, rather than purchased or processed foods).

When buying food, look at the fat content (over 17.5% is high fat content; 3-17.5% is moderate fat content; less than 3% is low fat; see the next page)

Avoid butter, cream, lard and high-fat cheese.

Cut down on oily curries, fish and chips, fry-ups, burgers.

Cut down on cakes, pastries, croissants, cookies and ice cream. Nothing needs to be treated as totally forbidden. A small portion of something as an occasional treat is perfectly OK.

But if there is something specific that triggers your attacks of pain (often this can be cheesy pasta, burgers, fry-up breakfasts, take-out curries), AVOID that at all costs.

How to cook

Trim all fat and skin off meat

When cooking vegetables or meat, try to boil, steam, grill, bake or shallow-fry in a non-stick pan rather than deep-fry or cook in a rich sauce.

Try and use low-fat alternatives where they exist. When baking cakes, half of the butter can usually be replaced by zero fat yogurt,

If you get an attack of biliary pain

For a mild attack, try Paracetamol or Ibuprofen (assuming you have no allergies to either of these drugs and no asthma) as well as some anti-acid medication (for example Gaviscon or Omeprazole). Buscopan may help too. Stronger painkillers like Co-codamol or Diclofenac should be used only if you have them at hand, and have taken them before. If the pain is very severe to start with or does not settle with these medications, please seek urgent medical help. Please remember – just because you have gallstones does not mean you cannot have other problems like angina or acid reflux.

Click here to view the list of the fat content of common food items.

What happens on the day, before the operation?

You will need to fast before the operation. This means nothing to eat for 6 hours before the operation, and nothing eat or drink (not even water) for 4 hours before the operation.

You will be expected to arrive at the hospital some hours before the scheduled time of your operation – this will be specified to you beforehand. Be there on time. Pack only enough stuff for a short stay. Pack a few days’ worth of your regular medications.

Please tell your doctors and nurses without fail

- If you have an allergy to a particular medication

- If you are (or might be) pregnant

- What medications you are on. You should have already stopped taking medicines that affect your clotting (such as heparin or warfarin).

If you are diabetic, you may need to skip the morning dose of your medications when you are fasting on the day of your operation. Please discuss this with your surgeon or nurse.

Most other regular medications can be taken with a sip of water a couple of hours before the operation.

Blood tests (and in some instances an ECG and a chest x ray) may be done after your admission if they have not been done before.

Your anaesthetist and a member of the surgical team will see you and explain what is going to be done. You will be required to sign a consent form.

Before your operation you will be required to change into a hospital gown and wear stockings. The stockings are to reduce the risk of blood clots forming in your legs. You may also receive an injection to slightly “thin” your blood (a low dose of heparin or something similar).

Will I need a blood transfusion?

Is it safe to have the operation as a "day case"?

Might I require open surgery? How often are keyhole operations converted to open operations?

If laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not possible, the gallbladder is removed by traditional open surgery, through a cut under the rib cage on the right side. What is done inside is exactly the same, but there is a bigger flesh wound, and therefore a longer convalescence, usually 3-5 days.

What if I have a stone in my bile duct?

Alternatively, if the surgeon thinks that there may be a stone in your bile duct, intra-operative cholangiography (an X-ray) can be carried out. If this is planned, it will be discussed with you before the operation. It involves putting a thin plastic tube into the bile duct during the operation. Some contrast material (dye that shows up on x-rays) is then injected into the duct and x-rays are taken in the operating room to get a view of the inside of the duct. It adds about 15-20 minutes to the operation. If the x-ray shows stones in the bile duct, the surgeon may decide to leave them there to be removed later by endoscopy (ERCP), or try to remove them immediately either by keyhole or open surgery. All of these are feasible options – the decision may depend on the size and number of stones and also on the degree of surgical and endoscopic expertise at hand.

Is it safe to have surgery if I have recently suffered from inflammation of the gall bladder?

Is it safe to have surgery while I am pregnant?

Here are a few general guidelines about surgery during pregnancy (other than obstetric operations):

- Elective (non-urgent) operations that can be safely postponed, should be postponed until after delivery.

- If possible, non-urgent surgery should be performed in the second trimester (i.e. months 4,5 and 6).

- A pregnant woman should never be denied emergency surgery for life-threatening conditions, regardless of where she is in the course of her pregnancy.

An obstetric specialist should be involved in the care of the patient.

Steps after gallstone surgery

Blank

What can I expect on the day, after the operation?

There will be some pain and sickness for 12 to 24 hours, but you will be given medications for this.

Some bruising and slight oozing of blood around the cuts is normal.

Once you are fully awake, you will be encouraged to walk around and drink fluids. You should then be able to eat something light a few hours later.

What can I expect after leaving hospital?

- What can I do or not do immediately after I return home?

- How soon can I return to work?

- When can I start exercising again?

- When can I drive again?

You will be given pain killers. Please take them as prescribed.

Ask your surgeon or nurse about the care of your wounds. In most instances your cuts will be closed with glue or with self-dissolving stitches under the skin. We advise our patients to keep the wounds dry for at least 24 hours; after that you can shower daily (do not soak in a bath until the wounds have completely dried).

If you find any redness or discharge in the wound, get a lot of pain, develop a fever, or develop jaundice, do see your GP urgently or contact your surgeon or the hospital, as these may be signs of a wound infection or other complications.

Some pain and mild bruising around the wounds is normal.

There are no dietary restrictions that you need to follow after this operation.

As for when you should return to work and resume exercise, discuss that with your surgeon or with your GP. Broadly speaking, physical activity should be gentle over the first 2-3 days. Most people are up and about the house the day after the operation. Returning to work depends on how quickly you recover and the nature of your work. Light work that involves sitting at a desk may be possible within a week. If your job involves heavy physical exertion or lifting, you should wait for at least 2 weeks, and possibly longer. If you want to go to the gym, wait for 2 weeks, and then re-start gently.

In general we suggest to our patients that they should not drive a vehicle for at least 2 weeks. You may wish to discuss this with your surgeon or your vehicle insurer. When recovering from a gall bladder operation, If doing something hurts your tummy, then stop doing it! Your body is telling you that it is not ready for that yet.

What complications might I suffer from the operation?

There some risks associated with the general anaesthetic, including pneumonia, heart problems, and blood clots in the leg veins and lungs.

Complications that may develop during or after the operation include bleeding, infection, injury to the liver or to an adjacent loop of bowel and, very rarely, pancreatitis.

The bile duct runs close to the gallbladder and there is a small risk of injury to the bile duct. The gallbladder is like a pear, hanging off a branch (the bile duct). The surgeon has to cut the “stalk of the pear”, without damaging the “branch”. Accidental injury to the bile duct may lead to a bile leak, or to jaundice due to a narrowing or blockage of the bile duct. It may need an endoscopy (ERCP), or even a major operation to repair it.

Occasionally, a stone may slip into the bile duct during the operation, and later cause pain or jaundice or abnormal blood tests. If that happens, it can usually be removed later by doing an ERCP.

How common is injury to the bile duct or other organs at the time of gall bladder surgery?

What symptoms should I look out for after the operation?

Can gallstones form again after the gall bladder has been removed?

If, months or years later, you develop a blockage in the flow of bile down the bile duct (such blockages can be due to inflammation, scarring, or a new growth), then stones can form in the duct.

If, for some reason, your surgeon was unable to remove your gall bladder completely and part of it was left behind, then you can develop further gallstones in that remnant gall bladder.

Do I need to modify my diet after the operation? Can I still eat everything if my gall bladder is removed?

Will I put on weight after my gall bladder is removed?

Will my bowels work as normal after the operation? Might I suffer from diarrhoea after my gall bladder is removed?

A small number of people develop frequent loose, watery stools after surgery to remove their gallbladders. In most cases, the diarrhoea resolves soon afterwards. Rarely, it may last longer.

The cause of diarrhoea after gallbladder removal is not known. It may be due to more bile acids entering the intestine and acting as a laxative.

Your doctor may advise you to:

- Try anti-diarrhoeal medications, such as loperamide or codeine

- Try medications that reduce the absorption of bile acids, such as cholestyramine or colesevelam

- Cut down on foods that can worsen diarrhea in general, including dairy products, very greasy or sweet foods, and caffeine.

If I have had my gall bladder removed but am still in pain, what should I do? What is the post-cholecystectomy syndrome?

The first thing to consider is were the initial symptoms caused not by the gallstones but by some other problem that was not picked up (such as acid reflux or a peptic ulcer or chronic pancreatitis)? Further tests may be required to diagnose these, for example an endoscopy.

The second possibility is that there may be a gallstone that has been left behind, perhaps in the bile duct. Blood tests and an ultrasound or MRCP scan can clarify this, and an endoscopic procedure (ERCP) can usually be done to remove the stone.

Other less common surgical complications can sometimes cause symptoms, such as a weakening of one of the scars, resulting in a small hernia (fat or bowel popping out) through the scar.

Sometimes the loss of the gall bladder may affect the functioning of the bowel. Bile refluxing back into the stomach may cause irritation of the stomach (gastritis) or the gullet (oesophagitis). Or diarrhoea may develop due to an excess of bile acid entering the bowel (see the previous section).

What if you take my gall bladder out for stones and then find I have a cancer of the gall bladder?

Another scenario is the unexpected finding of gall bladder cancer after what was thought to be a routine cholecystectomy for gallstones. Once the gall bladder has been removed, it is sent to the laboratory for the pathologist to examine it. Usually, the pathologist’s report confirms that the gall bladder showed signs of inflammation. Very rarely, the report says that there was a cancerous growth in the gall bladder! If gall bladder cancer is described in the pathologist’s report after a routine cholecystectomy, the two important questions are: How deeply had the tumour invaded through the gallbladder wall, and did it reach up to the surgical margins (the edges of the cut)? These are the two major indicators of prognosis. Simple cholecystectomy is adequate for T1 tumours, which are confined to the mucous membrane or the muscle layer deep to that, and further surgery is not necessary. For T2 tumours, which have gone through the muscle layer in the gall bladder wall, but not much further, a second operation may be necessary. For T3 and T4 tumours, where the tumour goes through the full thickness of the gall bladder wall, and for tumours where the surgical resection margins are involved, a second, more radical operation should certainly be considered. This may involve a resection of the part of the liver that adjoins the gall bladder (called an extended cholecystectomy) or even a formal excision of two liver segments (4b and 5), with removal of the regional lymph glands and part of the bile duct. The laparoscopic port sites (the entry points of the instruments) may also have to be excised.